The biggest difference between the questions used for most interviews and those used on questionnaires is that interviewing permits interaction between the questions and their meanings. In an interview the analyst has an opportunity to refine a question, define a muddy term, change the course of questioning, respond to a puzzled look, and generally control the context.

Few of these opportunities are possible on a questionnaire. Thus, for the analyst, questions must be transparently clear, the flow of the questionnaire cogent, the respondent’s questions anticipated, and the administration of the questionnaire planned in detail. (A respondent is the person who responds to or answers the questionnaire.)

The basic question types used on the questionnaire are open-ended and closed, as discussed for interviewing. Due to the constraints placed on questionnaires, some additional discussion of question types is warranted.

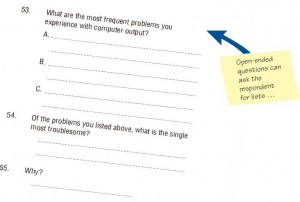

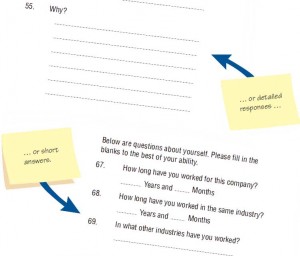

Open-Ended Questions

Recall that open-ended questions (or statements) are those that leave all possible response options open to the respondent. For example, open-ended questions on a questionnaire might read, “Describe any problems you are currently experiencing with output reports” or “In your opinion, how helpful are the user manuals for the current system’s accounting application?”

When you write open-ended questions for a questionnaire, anticipate what kind of response you will get. For instance, if you ask a question such as, “How do you feel about the system?” the responses are apt to be too broad for accurate interpretation or comparison. Therefore, even when you write an open-ended question, it must be narrow enough to guide respondents to answer in a specific way. (Examples of open-ended questions can be found in the figure right below.)

Open-ended questions are particularly well suited to situations in which you want to get at organizational members’ opinions about some aspect of the system, whether product or process. In such cases you will want to use open-ended questions when it is impossible to list effectively all the possible responses to the question.

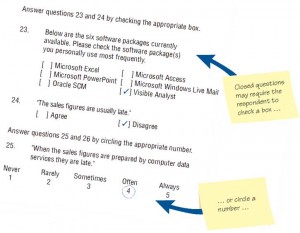

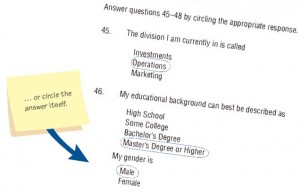

Closed Questions

Recall that closed questions (or statements) are those that limit or close the response options available to the respondent. For example, in the figure shown below the statement in question 23 (“Below are the six software packages currently available. Please check the software package(s) you personally use most frequently”) is closed. Notice that respondents are not asked why the package is preferred, nor are they asked to select more than one, even if that is a more representative response.

Closed questions should be used when the systems analyst is able to list effectively all the possible responses to the question and when all the listed responses are mutually exclusive, so that choosing one precludes choosing any of the others.

Use closed questions when you want to survey a large sample of people. The reason becomes obvious when you start imagining how the data you are collecting will look. If you use only open-ended questions for hundreds of people, correct analysis and interpretation of their responses becomes impossible without the aid of a computerized content analysis program.

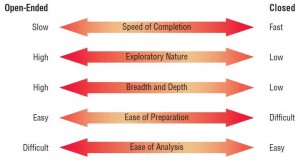

There are trade-offs involved in choosing either open-ended or closed questions for use on questionnaires. Figure shown below summarizes these trade-offs. Notice that responses to open-ended questions can help analysts gain rich, exploratory insights as well as breadth and depth on a topic. Although open-ended questions can be written easily, responses to them are difficult and time consuming to analyze.

When we refer to the writing of closed questions with either ordered or unordered answers, we often refer to the process as scaling. The use of scales in surveys is discussed in detail in a later section.

Word Choice

Just as with interviews, the language of questionnaires is an extremely important aspect of their effectiveness. Even if the systems analyst has a standard set of questions concerning systems development, it is wise to write them to reflect the business’s own terminology.

Respondents appreciate the efforts of someone who bothers to write a questionnaire reflecting their own language usage. For instance, if the business uses the term supervisors instead of managers, or units rather than departments, incorporating the preferred terms in the questionnaire helps respondents relate to the meaning of the questions. Responses will be easier to interpret accurately, and respondents will be more enthusiastic overall.

To check whether language used on the questionnaire is that of the respondents, try some sample questions on a pilot (test) group. Ask them to pay particular attention to the appropriateness of the wording and to change any words that do not ring true.

Here are some guidelines to use when choosing language for your questionnaire:

- Use the language of respondents whenever possible. Keep wording simple.

- Work at being specific rather than vague in wording.Avoid overly specific questions as well.

- Keep questions short.

- Do not patronize respondents by talking down to them through low-level language choices.

- Avoid bias in wording. Avoiding bias also means avoiding objectionable questions.

- Target questions to the correct respondents (that is, those who are capable of responding). Don’t assume too much knowledge.

- Ensure that questions are technically accurate before including them.

- Use software to check whether the reading level is appropriate for the respondents.

Contents

- Interviewing in Information Gathering

- Five Steps in Interview Preparation

- Open-Ended and Closed Type Interview Questions

- Arranging Interview Questions in a Logical Sequence

- Joint Application Design (JAD) in Information Gathering

- Using Questionnaires in Information Gathering

- Writing Questions for Questionnaires

- Using Scales in Questionnaires

- Designing and Administering the Questionnaires