Throughout this chapter we have referred to the systematic approach analysts take to the analysis and design of information systems. Much of this is embodied in what is called the systems development life cycle (SDLC). The SDLC is a phased approach to analysis and design that holds that systems are best developed through the use of a specific cycle of analyst and user activities.

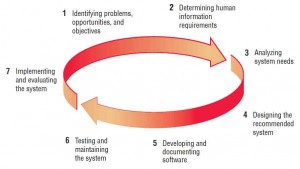

Analysts disagree on exactly how many phases there are in the SDLC, but they generally laud its organized approach. Here we have divided the cycle into seven phases, as shown in figure below. Although each phase is presented discretely, it is never accomplished as a separate step. Instead, several activities can occur simultaneously, and activities may be repeated.

Incorporating Human–Computer Interaction Considerations

In recent years, the study of human–computer interaction (HCI) has become increasingly important for systems analysts. Although the definition is still evolving, researchers characterize HCI as the “aspect of a computer that enables communications and interactions between humans and the computer. It is the layer of the computer that is between humans and the computer” (Zhang, Carey, Te’eni, & Tremaine, 2005, p. 518). Analysts using an HCI approach are emphasizing people rather than the work to be done or the IT that is involved. Their approach to a problem is multifaceted, looking at the “human ergonomic, cognitive, affective, and behavioral factors involved in user tasks, problem solving processes and interaction context” (Zhang, Carey, Te’eni, & Tremaine, 2005, p. 518). Human computer interaction moves away from focusing first on organizational and system needs and instead concentrates on human needs. Analysts adopting HCI principles examine a variety of user needs in the context of humans interacting with information technology to complete tasks and solve problems. These include taking into account physical or ergonomic factors; usability factors that are often labeled cognitive matters; the pleasing, aesthetic, and enjoyable aspects of using the system; and behavioral aspects that center on the usefulness of the system.

The seven phases of the systems development life cycle (SDLC).

Another way to think about HCI is to think of it as a human-centered approach that puts people ahead of organizational structure or culture when creating new systems. When analysts employ HCI as a lens to filter the world, their work will possess a different quality than the work of those who do not possess this perspective.

Your career can benefit from a strong grounding in HCI. The demand for analysts who are capable of incorporating HCI into the systems development process keeps rising, as companies increasingly realize that the quality of systems and the quality of work life can both be improved by taking a human-centered approach at the outset of a project.

The application of human–computer interaction principles tries to uncover and address the frustrations that users voice over their use of information technology. These concerns include a suspicion that systems analysts misunderstand the work being done, the tasks involved, and how they can best be supported; a feeling of helplessness or lack of control when working with the system; intentional breaches of privacy; trouble navigating through system screens and menus; and a general mismatch between the system designed and the way users themselves think of their work processes.

Misjudgments and errors in design that cause users to neglect new systems or that cause systems to fall into disuse soon after their implementation can be eradicated or minimized when systems analysts adopt an HCI approach.

Researchers in HCI see advantages to the inclusion of HCI in every phase of the SDLC. This is a worthwhile approach, and we will try to mirror this by bringing human concerns explicitly into each phase of the SDLC. As a person who is learning systems analysis, you can also bring a fresh eye to the SDLC to identify opportunities for designers to address HCI concerns and ways for users to become more central to each phase of the SDLC. Chapter 14 is devoted to examining the role of the systems analyst in designing human-centered systems and interfaces from an HCI perspective.

Identifying Problems, Opportunities, and Objectives in SDLC

In this first phase of the systems development life cycle, the analyst is concerned with correctly identifying problems, opportunities, and objectives. This stage is critical to the success of the rest of the project, because no one wants to waste subsequent time addressing the wrong problem. The first phase requires that the analyst look honestly at what is occurring in a business.

Then, together with other organizational members, the analyst pinpoints problems. Often others will bring up these problems, and they are the reason the analyst was initially called in. Opportunities are situations that the analyst believes can be improved through the use of computerized information systems. Seizing opportunities may allow the business to gain a competitive edge or set an industry standard.

Identifying objectives is also an important component of the first phase. The analyst must first discover what the business is trying to do. Then the analyst will be able to see whether some aspect of information systems applications can help the business reach its objectives by addressing specific problems or opportunities.

The people involved in the first phase are the users, analysts, and systems managers coordinating the project. Activities in this phase consist of interviewing user management, summarizing the knowledge obtained, estimating the scope of the project, and documenting the results. The output of this phase is a feasibility report containing a problem definition and summarizing the objectives. Management must then make a decision on whether to proceed with the proposed project. If the user group does not have sufficient funds in its budget or wishes to tackle unrelated problems, or if the problems do not require a computer system, a different solution may be recommended, and the systems project does not proceed any further.

Determining Human Information Requirements in System Development Life Cycle

The next phase the analyst enters is that of determining the human needs of the users involved, using a variety of tools to understand how users interact in the work context with their current information systems. The analyst will use interactive methods such as interviewing, sampling and investigating hard data, and questionnaires, along with unobtrusive methods, such as observing decision makers’ behavior and their office environments, and all-encompassing methods, such as prototyping.

The analyst will use these methods to pose and answer many questions concerning human-computer interaction (HCI), including questions such as, “What are the users’ physical strengths and limitations?” In other words, “What needs to be done to make the system audible, legible, and safe?” “How can the new system be designed to be easy to use, learn, and remember?” “How can the system be made pleasing or even fun to use?” “How can the system support a user’s individual work tasks and make them more productive in new ways?”

In the information requirements phase of the SDLC, the analyst is striving to understand what information users need to perform their jobs. At this point the analyst is examining how to make the system useful to the people involved. How can the system better support individual tasks that need doing? What new tasks are enabled by the new system that users were unable to do without it? How can the new system be created to extend a user’s capabilities beyond what the old system provided? How can the analyst create a system that is rewarding for workers to use?

The people involved in this phase are the analysts and users, typically operations managers and operations workers. The systems analyst needs to know the details of current system functions: the who (the people who are involved), what (the business activity), where (the environment in which the work takes place), when (the timing), and how (how the current procedures are performed) of the business under study. The analyst must then ask why the business uses the current system. There may be good reasons for doing business using the current methods, and these should be considered when designing any new system.

Agile development is an object-oriented approach (OOA) to systems development that includes a method of development (including generating information requirements) as well as software tools. In this text it is paired with prototyping in Chapter 6. (There is more about object-oriented approaches in Chapter 10.)

If the reason for current operations is that “it’s always been done that way,” however, the analyst may wish to improve on the procedures. At the completion of this phase, the analyst should understand how users accomplish their work when interacting with a computer and begin to know how to make the new system more useful and usable. The analyst should also know how the business functions and have complete information on the people, goals, data, and procedures involved.

Analyzing System Needs in System Development Life Cycle

The next phase that the systems analyst undertakes involves analyzing system needs. Again, special tools and techniques help the analyst make requirement determinations. Tools such as data flow diagrams (DFD) to chart the input, processes, and output of the business’s functions, or activity diagrams or sequence diagrams to show the sequence of events, illustrate systems in a structured, graphical form. From data flow, sequence, or other diagrams, a data dictionary is developed that lists all the data items used in the system, as well as their specifications.

During this phase the systems analyst also analyzes the structured decisions made. Structured decisions are those for which the conditions, condition alternatives, actions, and action rules can be determined. There are three major methods for analysis of structured decisions: structured English, decision tables, and decision trees.

At this point in the System Development Life Cycle (SDLC), the systems analyst prepares a systems proposal that summarizes what has been found out about the users, usability, and usefulness of current systems; provides cost-benefit analyses of alternatives; and makes recommendations on what (if anything) should be done. If one of the recommendations is acceptable to management, the analyst proceeds along that course. Each systems problem is unique, and there is never just one correct solution. The manner in which a recommendation or solution is formulated depends on the individual qualities and professional training of each analyst and the analyst’s interaction with users in the context of their work environment.

Designing the Recommended System

In the design phase of the System Development Life Cycle (SDLC), the systems analyst uses the information collected earlier to accomplish the logical design of the information system. The analyst designs procedures for users to help them accurately enter data so that data going into the information system are correct. In addition, the analyst provides for users to complete effective input to the information system by using techniques of good form and Web page or screen design.

Part of the logical design of the information system is devising the HCI. The interface connects the user with the system and is thus extremely important. The user interface is designed with the help of users to make sure that the system is audible, legible, and safe, as well as attractive and enjoyable to use. Examples of physical user interfaces include a keyboard (to type in questions and answers), onscreen menus (to elicit user commands), and a variety of graphical user interfaces (GUIs) that use a mouse or touch screen.

The design phase also includes designing databases that will store much of the data needed by decision makers in the organization. Users benefit from a well-organized database that is logical to them and corresponds to the way they view their work. In this phase the analyst also works with users to design output (either onscreen or printed) that meets their information needs. Finally, the analyst must design controls and backup procedures to protect the system and the data, and to produce program specification packets for programmers. Each packet should contain input and output layouts, file specifications, and processing details; it may also include decision trees or tables, UML or data flow diagrams, and the names and functions of any pre-written code that is either written in-house or using code or other class libraries.

Developing and Documenting Software

In the fifth phase of the SDLC, the analyst works with programmers to develop any original software that is needed. During this phase the analyst works with users to develop effective documentation for software, including procedure manuals, online help, and Web sites featuring Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs), on Read Me files shipped with new software. Because users are involved from the beginning, phase documentation should address the questions they have raised and solved jointly with the analyst. Documentation tells users how to use software and what to do if software problems occur.

Programmers have a key role in this phase because they design, code, and remove syntactical errors from computer programs. To ensure quality, a programmer may conduct either a design or a code walk-through, explaining complex portions of the program to a team of other programmers.

Testing and Maintaining the System

Before the information system can be used, it must be tested. It is much less costly to catch problems before the system is signed over to users. Some of the testing is completed by programmers alone, some of it by systems analysts in conjunction with programmers. A series of tests to pinpoint problems is run first with sample data and eventually with actual data from the current system. Often test plans are created early in the SDLC and are refined as the project progresses.

Maintenance of the system and its documentation begins in this phase and is carried out routinely throughout the life of the information system. Much of the programmer’s routine work consists of maintenance, and businesses spend a great deal of money on maintenance. Some maintenance, such as program updates, can be done automatically via a vendor site on the Web. Many of the systematic procedures the analyst employs throughout the SDLC can help ensure that maintenance is kept to a minimum.

Implementing and Evaluating the System in SDLC

In this last phase of systems development, the analyst helps implement the information system. This phase involves training users to handle the system. Vendors do some training, but oversight of training is the responsibility of the systems analyst. In addition, the analyst needs to plan for a smooth conversion from the old system to the new one. This process includes converting files from old formats to new ones, or building a database, installing equipment, and bringing the new system into production.

Evaluation is included as part of this final phase of the SDLC mostly for the sake of discussion. Actually, evaluation takes place during every phase. A key criterion that must be satisfied is whether the intended users are indeed using the system.

It should be noted that systems work is often cyclical. When an analyst finishes one phase of systems development and proceeds to the next, the discovery of a problem may force the analyst to return to the previous phase and modify the work done there.

The Impact of Maintenance

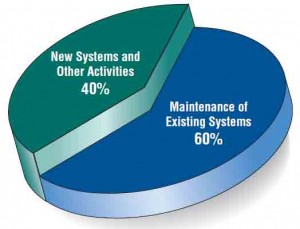

After the system is installed, it must be maintained, meaning that the computer programs must be modified and kept up to date. Figure Below illustrates the average amount of time spent on maintenance at a typical MIS installation. Estimates of the time spent by departments on maintenance have ranged from 48 to 60 percent of the total time spent developing systems. Very little time remains for new systems development. As the number of programs written increases, so does the amount of maintenance they require.

Some researchers estimate that the amount of time spent on system maintenance may be as much as 60 percent of the total time spent on systems projects.

Maintenance is performed for two reasons. The first of these is to correct software errors. No matter how thoroughly the system is tested, bugs or errors creep into computer programs. Bugs in commercial PC software are often documented as “known anomalies,” and are corrected when new versions of the software are released or in an interim release. In custom software (also called bespoke software), bugs must be corrected as they are detected.

The other reason for performing system maintenance is to enhance the software’s capabilities in response to changing organizational needs, generally involving one of the following three situations:

- Users often request additional features after they become familiar with the computer system and its capabilities.

- The business changes over time.

- Hardware and software are changing at an accelerated pace.

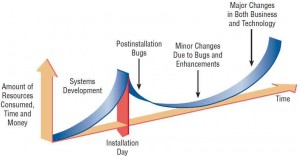

Figure below illustrates the amount of resources—usually time and money—spent on systems development and maintenance. The area under the curve represents the total dollar amount spent. You can see that over time the total cost of maintenance is likely to exceed that of systems development. At a certain point it becomes more feasible to perform a new systems study, because the cost of continued maintenance is clearly greater than that of creating an entirely new information system.

Resource consumption over the system life.

In summary, maintenance is an ongoing process over the life cycle of an information system. After the information system is installed, maintenance usually takes the form of correcting previously undetected program errors. Once these are corrected, the system approaches a steady state, providing dependable service to its users. Maintenance during this period may consist of removing a few previously undetected bugs and updating the system with a few minor enhancements. As time goes on and the business and technology change, however, the maintenance effort increases dramatically.

Contents

- Types of Systems

- Integrating Technologies for Systems

- Need for Systems Analysis and Design

- Roles of the Systems Analyst

- The Systems Development Life Cycle

- Using Computer-Aided Software Engineering (CASE) Tools

- The Agile Approach

- Object-Oriented Systems Analysis and Design & Choosing Which Systems Development Method to Use