To ensure the quality of data users enter into the system, it is important to capture data effectively. Data capture has received increasingly greater attention as the point in information processing at which excellent productivity gains can be made. Great progress in improving data capture has been made in the last four decades, as we have moved from multiple-step, slow, and error-prone systems such as keypunching to using sophisticated systems including such things as optical character recognition (OCR), bar codes, and point-of-sale terminals.

Deciding What to Capture

The decision about what to capture precedes user interaction with the system. Indeed, it is vital in making the eventual interface worthwhile, for the adage “garbage in, garbage out” is still true. Decisions about what data to capture for system input are made among systems analysts and systems users. Much of what will be captured is specific to the particular business. Capturing data, inputting them, storing them, and retrieving them are all costly endeavors. With all these factors in mind, determining what to capture becomes an important decision.

There are two types of data to enter: data that change or vary with every transaction, and data that concisely differentiate the particular item being processed from all other items.

An example of changeable data is the quantity of supplies purchased each time an advertising firm places an order with the office supply wholesaler. Because quantities change depending on the number of employees at the advertising firm and on how many accounts they are servicing, quantity data must be entered each time an order is placed.

An example of differentiation data is the inclusion on a patient record of the patient’s Social Security number and the first three letters of his or her last name. In this way, the patient is uniquely differentiated from other patients in the same system.

Letting the Computer Do the Rest

When considering what data to capture for each transaction and what data to leave to the system to enter, the systems analyst must take advantage of what computers do best. In the preceding example of the advertising agency ordering office supplies, it is not necessary for the operator entering the stationery order to reenter each item description each time an order is received. The computer can store and access this information easily.

Computers can automatically handle repetitive tasks, such as recording the time of the transaction, calculating new values from input, and storing and retrieving data on demand. By employing the best features of computers, efficient data capture design avoids needless data entry, which in turn alleviates much human error and boredom, and permits people to focus on higher-level or creative tasks. Software can be written to ask the user to enter today’s date or capture the date from the computer’s internal clock. Once entered, the system proceeds to use that date on all transactions processed in that data entry session.

A prime example of reusing data entered once is that of the online computer library center (OCLC) used by thousands of libraries in the United States. OCLC was built on the idea that each item bought by a library should only have to be cataloged once for all time. Once an item is entered, cataloging information goes into the huge OCLC database and is shared with participating libraries. In this case, implementation of the simple concept of entering data only once has saved enormous data entry time.

The calculating power of the computer should also be taken into account when deciding what not to reenter. Computers are adept at long calculations, using data already entered. For example, the person doing data entry may enter the flight numbers and account number of an air trip taken by a customer belonging to a frequent-flyer incentive program. The computer then calculates the number of miles accrued for each flight, adds it to the miles already in the customer’s account, and updates the total miles accrued to the account. The computer may also flag an account that, by virtue of the large number of miles flown, is now eligible for an award. Although all this information may appear on the customer’s updated account, the only new data entered were the flight numbers of the flights flown.

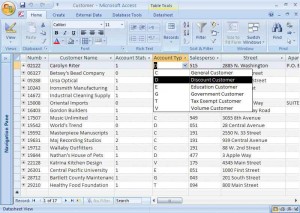

In systems that use a graphical user interface (GUI), codes are often stored either as a function or as a separate table in the database. There is a trade-off on creating too many tables, because the software must find matching records from each table, which may lead to slow access. If the codes are relatively stable and rarely change, they may be stored as a database function. If the codes change frequently, they are stored on a table so that they may be easily updated. Figure below shows how a drop-down list is used to select the codes for adding or changing a record in the CUSTOMER table. Notice that the code is stored, but the drop-down list displays both the code and the code meaning. This method helps to ensure accuracy, because the user does not have to guess at the meaning of the code and there is no chance of typing an invalid code.

Avoiding Bottlenecks and Extra Steps

A bottleneck in data entry is an apt allusion to the physical appearance of a bottle. Data are poured rapidly into the wide mouth of the system only to be slowed in its “neck” because of an artificially created instance of insufficient processing for the volume or detail of the data being entered. One way a bottleneck can be avoided is by ensuring that there is enough capacity to handle the data that are being entered.

Ways to avoid extra steps are determined not only at the time of analysis, but also when users begin to interact with prototypes of the system. The fewer steps involved in inputting data, the fewer chances there are for the introduction of errors. So, beyond the obvious consideration of saved labor, avoiding extra steps is also a way to preserve the quality of data. Once again, use of an online, real-time system that captures customer data without necessitating the completion of a form is an excellent example of saving steps in data entry.

Starting with a Good Form

Effective data capture is achievable only if prior thought is given to what the source document should contain. The data entry operator inputs data from the source document (usually some kind of form); this document is the source of a large amount of all system data. Online systems (or special data entry methods such as bar codes) may circumvent the need for a source document, but often some kind of paper form, such as a receipt, is created anyway.

With effective forms, it is not necessary to reenter information that the computer has already stored, or data such as time or date of entry that the computer can determine automatically. Chapter “Designing Effective Output” discussed in detail how a form or source document should be designed to maximize its usefulness for capturing data and to minimize the time users need to spend entering data from it.