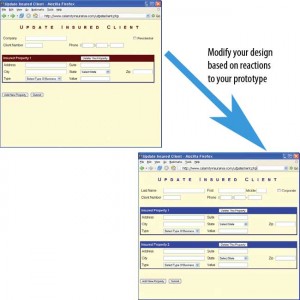

Prototyping is a superb way to elicit feedback about the proposed system and about how readily it is fulfilling the information needs of its users, as depicted in the figure illustrated below. The first step of prototyping is to estimate the costs involved in building a module of the system. If costs of programmers’ and analysts’ time as well as equipment costs are within the budget, building of the prototype can proceed. Prototyping is an excellent way to facilitate the integration of the information system into the larger system and culture of the organization.

Guidelines for Developing a Prototype

Once the decision to prototype has been made, four main guidelines must be observed when integrating prototyping into the requirements determination phase of the SDLC:

- Work in manageable modules.

- Build the prototype rapidly.

- Modify the prototype in successive iterations.

- Stress the user interface.

As you can see, the guidelines suggest ways of proceeding with the prototype that are necessarily interrelated. Each guideline is explained in the following subsections.

Working in manageable modules

When prototyping some of the features of a system into a workable model, it is imperative that the analyst work in manageable modules. One distinct advantage of prototyping is that it is not necessary or desirable to build an entire working system for prototype purposes.

A manageable module is one that allows users to interact with its key features but can be built separately from other system modules. Module features that are deemed less important are purposely left out of the initial prototype. As you will see later in this chapter, this is very similar to the agile approach that emphasizes small releases.

Building the prototype rapidly

Speed is essential to the successful prototyping of an information system. Recall that one complaint voiced against following the traditional SDLC is that the interval between requirements determination and delivery of a complete system is far too long to address evolving user needs effectively.

Analysts can use prototyping to shorten this gap by using traditional information-gathering techniques to pinpoint salient information requirements, and then quickly make decisions that bring forth a working model. In effect the user sees and uses the system very early in the SDLC instead of waiting for a finished system to gain hands-on experience.

Putting together an operational prototype both rapidly and early in the SDLC allows the analyst to gain valuable insight into how the remainder of the project should go. By showing users very early in the process how parts of the system actually perform, rapid prototyping guards against overcommitting resources to a project that may eventually become unworkable. Later, when RAD is discussed, you again see the importance of rapid systems building. In addition, agile modeling also builds on the practice of quick turnaround times.

Modifying the prototype

A third guideline for developing the prototype is that its construction must support modifications. Making the prototype modifiable means creating it in modules that are not highly interdependent. If this guideline is observed, less resistance is encountered when modifications in the prototype are necessary.

The prototype is generally modified several times, going through several iterations. Changes in the prototype should move the system closer to what users say is important. Each modification necessitates another evaluation by users.

The prototype is not a finished system. Entering the prototyping phase with the idea that the prototype will require modification is a helpful attitude that demonstrates to users how necessary their feedback is if the system is to improve.

Stressing the user interface

The user’s interface with the prototype (and eventually the system) is very important. Because what you are really trying to achieve with the prototype is to get users to further articulate their information requirements, they must be able to interact easily with the system’s prototype. They should be able to see how the prototype will enable them to accomplish their tasks. For many users the interface is the system. It should not be a stumbling block.

Although many aspects of the system will remain undeveloped in the prototype, the user interface must be well developed enough to enable users to pick up the system quickly and not be put off. Online, interactive systems using GUI interfaces are ideally suited to prototypes. Chapter 14 describes in detail the considerations that are important in designing HCI.

Disadvantages of Prototyping

As with any information-gathering technique, there are several disadvantages to prototyping. The first is that it can be quite difficult to manage prototyping as a project in the larger systems effort.

The second disadvantage is that users and analysts may adopt a prototype as a completed system when it is in fact inadequate and was never intended to serve as a finished system. Analysts need to work to ensure that communication with users is clear regarding the timetable for interacting with and improving the prototype.

The analyst needs to weigh these disadvantages against the known advantages when deciding whether to prototype, when to prototype, and how much of the system to prototype.

Advantages of Prototyping

Prototyping is not necessary or appropriate in every systems project, as we have seen. The advantages, however, should also be given consideration when deciding whether to prototype. The three major advantages of prototyping are the potential for changing the system early in its development, the opportunity to stop development on a system that is not working, and the possibility of developing a system that more closely addresses users’ needs and expectations.

Successful prototyping depends on early and frequent user feedback, which analysts can use to modify the system and make it more responsive to actual needs. As with any systems effort, early changes are less expensive than changes made late in the project’s development. In the later part of the chapter, you will see how the agile approach to development uses an extreme form of prototyping that requires an on-site customer to provide feedback during all iterations.

Prototyping Using COTS Software

Sometimes the quickest way to prototype is through the modular installation of COTS software. Although the concept of COTS software can be easily grasped by looking at familiar and relatively inexpensive packages such as the Microsoft Office products, some COTS software is elaborate and expensive, but highly useful. One example of rapid implementation of COTS software can be found in Catholic University’s use of the ERP COTS software package called PeopleSoft, which is handling many of its Web-based functions.

Catholic University, along with a higher education consulting group and PeopleSoft, successfully undertook rapid implementation of a recruiting and admissions module of their COTS software. They launched the implementation in April 1999, and by that October they had successfully implemented recruiting and admissions for undergraduates. By November of the same year, they implemented the same functions for graduate students. Other modules of the PeopleSoft COTS software that are implemented at Catholic University include a complete online course catalog, online registration, and the capability for students to check grades, transcripts, bills, and financial aid payments online from anywhere.

Contents

- Prototyping: Kinds of Prototypes

- Developing a Prototype: Guidelines

- Users’ Role in Prototyping

- Rapid Application Development (RAD)

- Comparing RAD to the SDLC

- Agile Modeling : Values and Principles of Agile Modeling

- Activities, Resources, and Practices of Agile Modeling

- The Agile Development Process

- Lessons Learned from Agile Modeling

- Improving Efficiency in Knowledge Work: SDLC Vs Agile

- Risks Inherent in Organizational Innovation