The following example is intended to illustrate the development of a data flow diagram by selectively looking at each of the components explored earlier in this chapter. This example, called “World’s Trend Catalog Division,” will also be used to illustrate concepts covered in Chapters 8 and 9.

Developing the List of Business Activities

A list of business activities for World’s Trend can be found in the illustration below. You could develop this list using information obtained through interacting with people in interviews, through investigation, and through observation. The list can be used to identify external entities such as CUSTOMER, ACCOUNTING, and WAREHOUSE as well as data flows such as ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE REPORT and CUSTOMER BILLING STATEMENT. Later (when developing level 0 and child diagrams), the list can be used to define processes, data flows, and data stores.

| World’s Trend |

|---|

World’s Trend - 1000 International Lane Cornwall, CT 06050 World’s Trend is a mail order supplier of high-quality, fashionable clothing. Customers place orders by telephone, by mailing an order form included with each catalog, or via the Web site. Summary of Business Activities

|

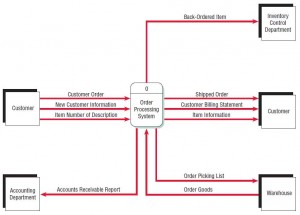

Creating a Context-level Data Flow Diagram

Once this list of activities is developed, create a context-level data flow diagram as shown in Figure 1. This diagram shows the ORDER PROCESSING SYSTEM in the middle (no processes are described in detail in the context-level diagram) and five external entities (the two separate entities both called CUSTOMER are really one and the same). The data flows that come from and go to the external entities are shown as well (for example, CUSTOMER ORDER and ORDER PICKING LIST).

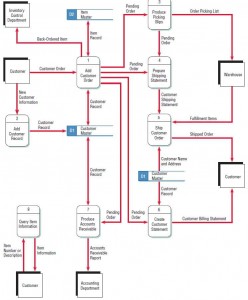

Drawing Diagram 0

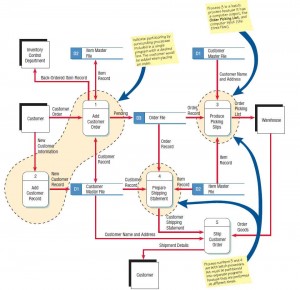

Next, go back to the activity list and make a new list of as many processes and data stores as you can find.You can add more later, but start making the list now. If you think you have enough information, draw a level 0 diagram such as the one found in Figure 2. Call this Diagram 0 and keep the processes general so as not to overcomplicate the diagram. Later, you can add detail.

When you are finished drawing the seven processes, draw data flows between them and to the external entities (the same external entities shown in the context-level diagram). If you think there need to be data stores such as ITEM MASTER or CUSTOMER MASTER, draw those in and connect them to processes using data flows. Now take the time to number the processes and data stores. Pay particular attention to making the labels meaningful. Check for errors and correct them before moving on.

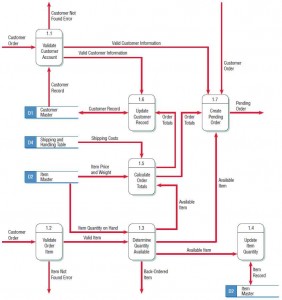

Creating a Child Diagram

At this point try to draw a child diagram (sometimes also called a level 1 diagram) such as the one in Figure 3. Child diagram processes are more detailed, illustrating the logic required to produce the output. Number your child diagrams Diagram 1, Diagram 2, and so on, in accordance with the number you assigned to each process in the level 0 diagram.

When you draw a child diagram, make a list of subprocesses first. A process such as ADD CUSTOMER ORDER can have subprocesses (in this case, there are seven). Connect these subprocesses to one another and also to data stores when appropriate. Subprocesses do not have to be connected to external entities, because we can always refer to the parent (or level 0) data flow diagram to identify these entities. Label the subprocesses 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, and so on. Take the time to check for errors and make sure the labels make sense.

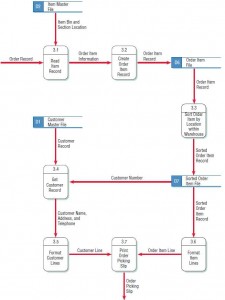

Creating a Physical Data Flow Diagram from the Logical DFD

If you want to go beyond the logical model and draw a physical model as well, look at Figure 4, which is an example of a physical data flow child diagram of process 3, PRODUCE PICKING SLIPS. Physical DFDs give you the opportunity to identify processes for scanning bar codes, displaying screens, locating records, and creating and updating files. The sequence of activities is important in physical DFDs, because the emphasis is on how the system will work and in what order events happen.

When you label a physical model, take care to describe the process in great detail. For example, subprocess 3.3 in a logical model could simply be SORT ORDER ITEM, but in the physical model, a better label is SORT ORDER ITEM BYLOCATION WITHIN CUSTOMER. When you write a label for a data store, refer to the actual file or database, such as CUSTOMER MASTER FILE or SORTED ORDER ITEM FILE. When you describe data flows, describe the actual form, report, or screen. For example, when you print a slip for order picking, call the data flow ORDER PICKING SLIP.

Partitioning the Physical DFD

Finally, take the physical data flow diagram and suggest partitioning through combining or separating the processes. As stated earlier, there are many reasons for partitioning: identifying distinct processes for different user groups, separating processes that need to be performed at different times, grouping similar tasks, grouping processes for efficiency, combining processes for consistency, or separating them for security. Figure 5 shows that partitioning is useful in the case of World’s Trend Catalog Division. You would first group processes 1 and 2 because it would make sense to add new customers at the same time their first order was placed. You would then put processes 3 and 4 in two separate partitions because these must be done at different times from each other and thus cannot be grouped into a single program.

The process of developing a data flow diagram is now completed from the top down, first drawing a companion physical data flow diagram to accompany the logical data flow diagram, then partitioning the data flow diagram by grouping or separating the processes. The World’s Trend example is used again in Chapters 8 and 9.