Creating the Project Charter

Part of the planning process is to agree on what will be done and at what time. Analysts who are external consultants, as well as those who are organization members, need to specify what they will eventually deliver and when they will deliver it. This chapter has elaborated on ways to estimate the delivery date for the completed system and also how to identify organizational goals and assess the feasibility of the proposed system.

The project charter is a written narrative that clarifies the following questions:

- What does the user expect of the project (what are the objectives)? What will the system do to meet the needs (achieve the objectives)?

- What is the scope (or what are the boundaries) of the project? (What does the user consider to be beyond the project’s reach?)

- What analysis methods will the analyst use to interact with users in gathering data, developing, and testing the system?

- Who are the key participants? How much time are users willing and able to commit to participating?

- What are the project deliverables? (What new or updated software, hardware, procedures, and documentation do the users expect to have available for interaction when the project is done?)

- Who will evaluate the system and how will they evaluate it? What are the steps in the assessment process? How will the results be communicated and to whom?

- What is the estimated project timeline? How often will analysts report project milestones?

- Who will train the users?

- Who will maintain the system?

The project charter describes in a written document the expected results of the systems project (deliverables) and the time frame for delivery. It essentially becomes a contract between the chief analyst (or project manager) and their analysis team with the organizational users requesting the new system.

Avoiding Project Failures

The early discussions you have with management and others requesting a project, along with the feasibility studies you do, are usually the best defenses possible against taking on projects that have a high probability of failure. Your training and experience will improve your ability to judge the worthiness of projects and the motivations that prompt others to request projects. If you are part of an in-house systems analysis team, you must keep current with the political climate of the organization as well as with financial and competitive situations.

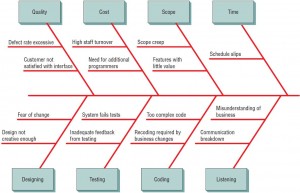

It is important, however, to note that systems projects can and do have serious problems. Those that are developed using agile methods are not immune to such troubles. In order to illustrate what can go wrong in a project, a systems analyst may want to draw a fishbone diagram (also called a cause-and-effect diagram or an Ishikawa diagram). When you examine the figure shown below, you will see that it is called a fishbone diagram because it resembles the skeleton of a fish.

The value of fishbone diagrams is to systematically list all the possible problems that can occur. In the case of the agile approach, it is useful to organize the fishbone diagram by listing all the resource control variables on the top and all the activities on the bottom. Some problems such as schedule slips might be obvious, but others such as scope creep (the desire to add features after the analyst hears new stories) or developing features with little value are not as obvious.

You can also learn from the wisdom gained by people involved in earlier project failures. When asked to reflect on why projects had failed, professional programmers cited the setting of impossible or unrealistic dates for completion by management, belief in the myth that simply adding more people to a project would expedite it (even though the original target date on the project was unrealistic), and management behaving unreasonably by forbidding the team to seek professional expertise from outside of the group to help solve specific problems.

Remember that you are not alone in the decision to begin a project. Although apprised of your team’s recommendations, management will have the final say about whether a proposed project is worthy of further study (that is, further investment of resources). The decision process of your team must be open and stand up to scrutiny from those outside of it. The team members should consider that their reputation and standing in the organization are inseparable from the projects they accept.

Contents

- Project Initiation

- Defining the Problem in Project Initiation

- Selection of Projects

- Feasibility Study – Determining Whether the Project is Feasible

- Technical Feasibility – Ascertaining Hardware and Software Needs

- Acquisition of Computer Equipment – Technical Feasibility

- Software Evaluation in Technical Feasibility

- Economic Feasibility – Identifying & Forecasting Costs & Benefits

- Comparing Costs and Benefits – Economic Feasibilty

- Activity Planning and Control – Project Management

- Using PERT Diagrams in Project Planning

- Managing the Project

- Managing Analysis and Design Activities

- Creating the Project Charter & Avoiding Project Failures

- Organizing the Systems Proposal

- Using Figures for Effective Communication in System Proposal