There are many well-known techniques for comparing the costs and benefits of the proposed system. They include break-even analysis, payback, cash-flow analysis, and present value analysis. All these techniques provide straightforward ways of yielding information to decision makers about the worthiness of the proposed system.

Break-Even Analysis

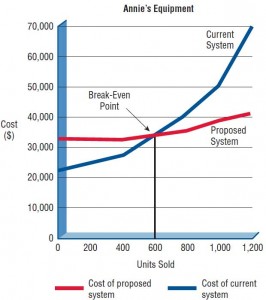

By comparing costs alone, the systems analyst can use break-even analysis to determine the break-even capacity of the proposed information system. The point at which the total costs of the current system and the proposed system intersect represents the break-even point, the point where it becomes profitable for the business to get the new information system.

Total costs include the costs that recur during operation of the system plus the developmental costs that occur only once (one-time costs of installing a new system), that is, the tangible costs that were just discussed. Figure 1 is an example of a break-even analysis on a small store that maintains inventory using a manual system. As volume rises, the costs of the manual system rise at an increasing rate. A new computer system would cost a substantial sum up front, but the incremental costs for higher volume would be rather small. The graph shows that the computer system would be cost effective if the business sold about 600 units per week.

Break-even analysis is useful when a business is growing and volume is a key variable in costs. One disadvantage of break-even analysis is that benefits are assumed to remain the same, regardless of which system is in place. From our study of tangible and intangible benefits, we know that is clearly not the case.

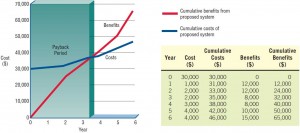

Break-even analysis can also determine how long it will take for the benefits of the system to pay back the costs of developing it. Figure 2 illustrates a system with a payback period of three and a half years.

Cash-Flow Analysis

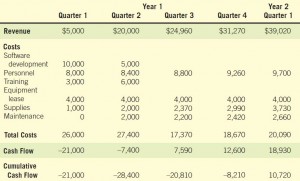

Cash-flow analysis examines the direction, size, and pattern of cash flow that is associated with the proposed information system. If you are proposing the replacement of an old information system with a new one and if the new information system will not be generating any additional cash for the business, only cash outlays are associated with the project. If that is the case, the new system cannot be justified on the basis of new revenues generated and must be examined closely for other tangible benefits if it is to be pursued further.

Figure 3 shows a cash-flow analysis for a small company that is providing a mailing service to other small companies in the city. Revenue projections are that only $5,000 will be generated in the first quarter, but after the second quarter, revenue will grow at a steady rate. Costs will be large in the first two quarters and then level off. Cash-flow analysis is used to determine when a company will begin to make a profit (in this case, it is in the third quarter, with a cash flow of $7,590) and when it will be “out of the red,” that is, when revenue has made up for the initial investment (in the first quarter of the second year, when accumulated cash flow changes from a negative amount to a positive $10,720).

The proposed system should have increased revenues along with cash outlays. Then the size of the cash flow must be analyzed along with the patterns of cash flow associated with the purchase of the new system. You must ask when cash outlays and revenues will occur, not only for the initial purchase but also over the life of the information system.

Present Value Analysis

Present value analysis helps the systems analyst to present to business decision makers the time value of the investment in the information system as well as the cash flow (as discussed in the previous section). Present value is a way to assess all the economic outlays and revenues of the information system over its economic life, and to compare costs today with future costs and today’s benefits with future benefits.

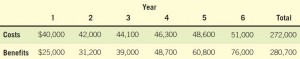

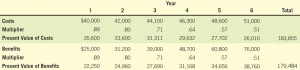

In Figure 4, system costs total $272,000 over six years and benefits total $280,700. Therefore, we might conclude that benefits outweigh the costs. Benefits only started to surpass costs after the fourth year, however, and dollars in the sixth year will not be equivalent to dollars in the first year.

For instance, a dollar investment at 7 percent today will be worth $1.07 at the end of the year and will double in approximately 10 years. The present value, therefore, is the cost or benefit measured in today’s dollars and depends on the cost of money. The cost of money is the opportunity cost, or the rate that could be obtained if the money invested in the proposed system were invested in another (relatively safe) project.

The present value of $1.00 at a discount rate of i is calculated by determining the factor

1

______

(1 + i )n

where n is the number of periods. Then the factor is multiplied by the dollar amount, yielding the present value as shown in Figure 5. In this example, the cost of money—the discount rate—is assumed to be .12 (12 percent) for the entire planning horizon. Multipliers are calculated for each period: n = 1, n = 2, …, n = 6. Present values of both costs and benefits are then calculated using these multipliers. When that step is done, the total benefits (measured in today’s dollars) are $179,484, and thus less than the costs (also measured in today’s dollars). The conclusion to be drawn is that the proposed system is not worthwhile if present value is considered.

Although this example, which used present value factors, is useful in explaining the concept, all electronic spreadsheets have a built-in present value function. The analyst can directly compute present value using this feature.

Guidelines for Analysis

The use of the methods discussed in the preceding subsections depends on the methods employed and accepted in the organization itself. For general guidelines, however, it is safe to say the following:

- Use break-even analysis if the project needs to be justified in terms of cost, not benefits, or if benefits do not substantially improve with the proposed system.

- Use payback when the improved tangible benefits form a convincing argument for the proposed system.

- Use cash-flow analysis when the project is expensive relative to the size of the company or when the business would be significantly affected by a large drain (even if temporary) on funds.

- Use present value analysis when the payback period is long or when the cost of borrowing money is high.

Whichever method is chosen, it is important to remember that cost-benefit analysis should be approached systematically, in a way that can be explained and justified to managers, who will eventually decide whether to commit resources to the systems project. Next, we turn to the importance of comparing many systems alternatives.

Contents

- Project Initiation

- Defining the Problem in Project Initiation

- Selection of Projects

- Feasibility Study – Determining Whether the Project is Feasible

- Technical Feasibility – Ascertaining Hardware and Software Needs

- Acquisition of Computer Equipment – Technical Feasibility

- Software Evaluation in Technical Feasibility

- Economic Feasibility – Identifying & Forecasting Costs & Benefits

- Comparing Costs and Benefits – Economic Feasibilty

- Activity Planning and Control – Project Management

- Using PERT Diagrams in Project Planning

- Managing the Project

- Managing Analysis and Design Activities

- Creating the Project Charter & Avoiding Project Failures

- Organizing the Systems Proposal

- Using Figures for Effective Communication in System Proposal